Alexander the Great and the Book of Daniel: A Providential Encounter in Josephus

In the Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition, the Book of Daniel holds a central place among the prophetic writings of the Old Testament. Revealed to the holy prophet Daniel during the Babylonian captivity, it unveils divine mysteries concerning the succession of empires, the coming trials of God’s people, and ultimately the establishment of the everlasting Kingdom of the Messiah. Orthodox saints and Fathers, such as St. Jerome and St. John Chrysostom, have expounded its visions as genuine prophecies inspired by the Holy Spirit, foretelling events centuries in advance with remarkable precision. Among these is the rise of a mighty Greek king who would overthrow the Persian Empire—a prophecy fulfilled in Alexander the Great (Daniel 8:5–8, 21; 11:3).

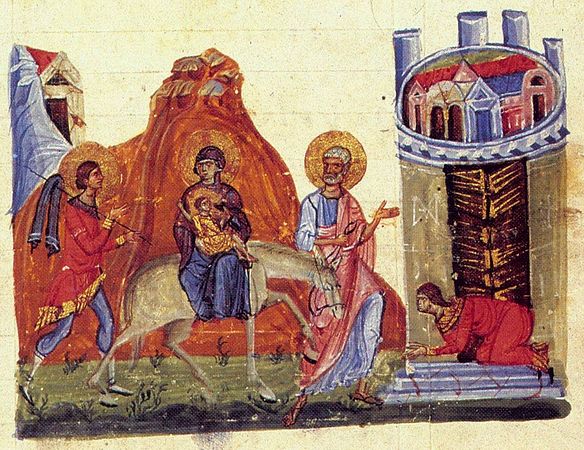

The first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, in his *Antiquities of the Jews* (Book 11, Chapter 8), recounts a striking episode that brings this prophecy to life. After conquering Tyre and Gaza in 332 BC, Alexander approached Jerusalem intending punishment, for the high priest Jaddua (or Jaddus) had refused aid, remaining loyal to the Persian king Darius. Alarmed, Jaddua prayed fervently and, guided by a divine dream, adorned the city and led a procession of priests in sacred vestments to meet the conqueror.

To the astonishment of Alexander’s generals, the king dismounted, prostrated himself before the high priest, and revered the name of God inscribed on his mitre. Alexander explained that in Macedonia, he had dreamed of this very priest, who promised him victory over the Persians under divine guidance. Entering Jerusalem peacefully, Alexander offered sacrifice in the Temple according to the high priest’s direction. There, Jaddua showed him the Book of Daniel, where it is written of a Greek who would shatter Persian dominion. Alexander rejoiced, recognizing himself as the fulfillment, and granted the Jews extensive favors: freedom to live by their ancestral laws, tax exemptions in sabbatical years, and similar privileges for Jews in Babylon and Media.

From an Orthodox perspective, this account—whether fully historical in every detail or enriched by pious tradition—beautifully illustrates God’s providence over His people and the truth of biblical prophecy. Alexander, a pagan ruler raised up by God “like a goat from the west” (Daniel 8:5), unwittingly fulfills the divine plan. His reverence for the God of Israel echoes Cyrus the Persian (Isaiah 45), whom the Lord called His “anointed” despite his ignorance. The story underscores that no empire rises or falls without God’s permission, and that sacred Scripture contains foreknowledge granted only by the Holy Spirit.

Evaluating Historicity and Credibility

Scholarly opinion on the historicity of Josephus’ narrative is divided, but the Orthodox faithful approach such matters with discernment, prioritizing the spiritual truth of Scripture over secular historical debates.

– Arguments for historicity: Josephus, a respected historian writing for a Greco-Roman audience, presents the story matter-of-factly, drawing perhaps from temple records or oral traditions. No ancient source directly contradicts it, and Alexander’s rapid conquests left room for detours (e.g., after Gaza). His known tolerance for local religions aligns with favoring the Jews, and the account explains Jewish privileges under early Hellenistic rule. Some conservative scholars and Orthodox interpreters see it as plausible evidence that Daniel’s prophecies were known and revered centuries before the Maccabean era.

– Arguments against: Most modern scholars regard the tale as legendary or apocryphal. No contemporary sources (e.g., Arrian, Plutarch, or Curtius Rufus) mention Alexander visiting Jerusalem, focusing instead on his major campaigns. Chronological issues arise with the high priest’s identity (Jaddua appears in Nehemiah, centuries earlier), and elements like the dream and prostration resemble Hellenistic romance motifs. The explicit reference to Daniel may be Josephus’ addition to affirm the book’s antiquity, countering views that it was composed later (2nd century BC). The narrative’s pro-Jewish, anti-Samaritan tone suggests it served apologetic purposes, contrasting Jewish fidelity with Samaritan opportunism.

The consensus among secular historians is that the core story is unhistorical—a pious legend that emerged to exalt Jewish identity under Hellenistic and Roman rule. Yet, even critics acknowledge Josephus believed Daniel predated Alexander, reflecting first-century Jewish conviction in its prophetic nature.

The Importance of the Account

Regardless of historical debates, the story’s enduring value lies in its theological witness. In Orthodox teaching, prophecy is not mere prediction but revelation of God’s sovereignty over history. Daniel’s visions— the ram (Persia) struck by the goat (Greece), the great horn broken and replaced by four (Alexander’s death and divided empire)—demonstrate that worldly powers are transient instruments in the divine plan, pointing toward the “stone cut without hands” (Daniel 2:34–45), the Kingdom of Christ.

This episode, preserved by Josephus and echoed in patristic writings, affirms the inspiration of Daniel and the continuity of God’s care for His covenant people. It reminds us that even mighty conquerors bow before the Almighty, and that Scripture’s prophecies are fulfilled in ways that glorify God. As St. Paul writes, “The Scriptures, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith” (Galatians 3:8), so too Daniel foresaw the Greek era as a step toward the Incarnation.

In the Orthodox Church, we receive such traditions prayerfully, discerning what edifies faith. Whether Alexander literally beheld Daniel’s scroll or not, the prophecy stands fulfilled, and God’s word endures forever. Glory to Him who reveals the future to His servants!