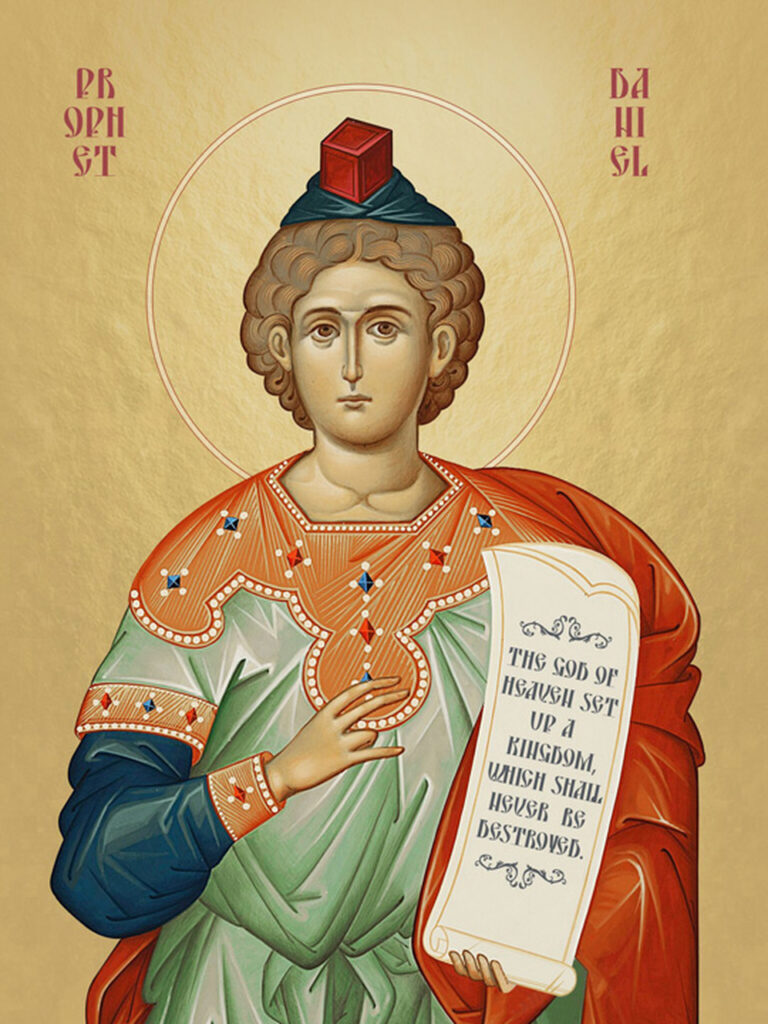

In the Book of the Prophet Daniel, chapter 2, we encounter an often-overlooked moment following the revelation and interpretation of King Nebuchadnezzar’s dream. The text states:

Then King Nebuchadnezzar fell on his face, prostrate before Daniel, and commanded that incense be offered to him. The king answered Daniel, and said, “Truly your God is the God of gods, the Lord of kings, and a revealer of mysteries, since you have been able to reveal this mystery.” (Daniel 2:46-47)

Here, the pagan king prostrates himself before the prophet Daniel and orders incense and offerings in his honor. Remarkably, the sacred text records no objection or rebuke from Daniel—a man renowned for his unwavering fidelity to God, even in the face of death (as seen in his refusal of defiled food in Daniel 1, his bold prayers despite prohibition in Daniel 6, and his companions’ defiance of idolatrous worship in Daniel 3). This silence has puzzled many commentators across traditions (even Chrysostom), who struggled to reconcile this scene with the strict prohibition against idolatry. From an Eastern Orthodox Christian perspective, however, the passage is not problematic but rather instructive, revealing the distinction between idolatrous worship and legitimate cultural gestures of profound honor directed ultimately toward God.

First, Daniel’s lack of rejection seems, at first glance, out of character for a prophet who consistently demonstrates extraordinary courage and zeal for God’s exclusive worship. Throughout the book, Daniel risks his life to avoid even the appearance of compromising his faith. He and his friends refuse the king’s food lest they be defiled (Dan. 1:8-16); they refuse to bow to Nebuchadnezzar’s golden image, facing the fiery furnace (Dan. 3); and Daniel continues praying to God alone, defying the royal decree and entering the lions’ den (Dan. 6). Given this pattern, one might expect Daniel to immediately repudiate any act resembling worship, as the apostles Peter and Paul later do when mistaken for divine beings (Acts 10:25-26; 14:11-18). Many Western commentators, particularly from Protestant traditions influenced by iconoclastic views, have indeed found this difficult to explain, often suggesting Daniel must have privately corrected the king or that the act was merely civil homage. Yet the text is silent on any correction, implying acceptance.

The key lies in understanding the cultural and biblical context of prostration and incense offerings. In the ancient Near East, falling prostrate and offering incense were traditional gestures of the highest respect and honor, not necessarily divine worship. Prostration appears frequently in Scripture as a sign of reverence toward human authorities without implying idolatry. For instance, Abraham bows before the Hittites (Gen. 23:7,12); Lot bows before visitors (angels, Gen. 19:1); Joseph’s brothers bow before him (Gen. 42:6; 43:28); Ruth bows before Boaz (Ruth 2:10); and David bows before King Saul (1 Sam. 24:8). Even in royal contexts, subjects prostrate before kings as a sign of submission and gratitude. Incense, similarly, was a customary offering in Babylonian and later Roman imperial culture to honor distinguished individuals or dignitaries, akin to lavish gifts or public acclaim—distinct from the sacrificial offerings reserved for deities.

Daniel, wise and discerning, would have recognized the king’s actions as an extravagant cultural expression of gratitude and honor for the divine revelation granted through him, rather than an attempt to deify Daniel himself. This is confirmed immediately in the text: Nebuchadnezzar does not exalt Daniel as a god but declares, “Truly your God is the God of gods, the Lord of kings, and a revealer of mysteries.” The honor bestowed on Daniel points directly to the true source—the God of Israel—as its ultimate object. Daniel receives it as God’s servant, through whom the Lord has manifested His supremacy over pagan wisdom and power. The prophet’s silence indicates he perceived no idolatrous intent; to reject it harshly might have undermined the very witness to God’s glory that the moment achieved.

This episode finds an echo in our Orthodox Christian tradition, which carefully distinguishes between latreia (worship due to God alone) and proskuneo (sometimes dulia) (veneration or honor given to saints, icons, and holy things). In Orthodox practice, incense is offered in divine liturgy as part of worship to God, symbolizing prayers rising heavenward (as in Ps. 141:2; Rev. 8:3-4). Yet incense is also censed toward icons, relics of saints (both living and reposed), clergy, and the faithful—not as worship of created things, but as honor reflecting God’s grace working through them. We honor the saints because God is “wonderful in His saints” (Ps. 68:35) and “glorious in His saints” (as echoed in Orthodox hymnody). Bowing respectfully before icons or bishops similarly expresses reverence, not divinity, and reflects a more ancient (and biblical) cultural of ‘relative veneration’ for which the ultimate intent and object is God (specifically God the Father).

The case of Daniel prefigures this: the king’s prostration and incense honor the prophet in whom God has revealed Himself, without idolatry. Just as Nebuchadnezzar glorifies “the God of Daniel,” so Orthodox veneration of saints directs honor ultimately to God, who crowns His faithful ones with glory. The text’s inescapable clarity—that this was not received as idolatrous by the prophet—affirms the biblical precedent for such distinctions. Far from a compromise, Daniel’s acceptance testifies to godly wisdom: discerning intent, avoiding unnecessary offense to a king newly awakened to divine truth, and allowing the honor to redound to God’s praise.

In our own time, this passage reminds Orthodox Christians to honor those through whom God works—our spiritual fathers, martyrs, and saints— at times with incense, prostrations, and hymns, always mindful that true worship belongs to God alone. As St. John of Damascus defended against iconoclasm, honor shown to the image passes to the prototype. So too with Daniel: the king’s gesture honored the man, but glorified the God who is wonderful in His prophets. May we, like Daniel, bear witness boldly, receiving honor humbly when it magnifies the Lord.