Introduction

The veneration of holy icons stands as a cornerstone of Orthodox Christian worship, embodying a profound theological reality rooted in Scripture and the apostolic tradition. Far from being a late innovation or a concession to paganism, as iconoclasts have claimed, the use of icons reflects the biblical understanding of creation, incarnation, and the economy of salvation. This paper defends the Orthodox theology of icons as inherently biblical and apostolic by examining seven key arguments drawn from Holy Scripture, patristic interpretations, and historical evidence. These points demonstrate that icons are not idols but visible expressions of the invisible divine realities, directing all honor ultimately to God the Father through His Son in the Holy Spirit.

1. Adam as the Icon of God and Worthy of Veneration

The foundational biblical affirmation that humanity is created in the “image” (EiKwv, eikon) of God (Genesis 1:26-27) establishes the theological basis for icons. Adam, as the first human, embodies this iconic status, serving as a visible representation of the invisible God. This image-bearing quality renders Adam worthy of veneration or homage from the angelic hosts, as reflected in Deuteronomy 32:43 from the Septuagint (LXX): “Rejoice, 0 heavens, with him, and let all the sons of God bow down to him.11 This verse, echoed in Hebrews 1:6

-“And let all God’s angels worship him”-is interpreted in Orthodox tradition as applying not only to Christ but analogously to Adam as God’s image-bearer, foreshadowing the incarnate Son.

This understanding is enriched by apocryphal and traditional accounts, such as the Life of Adam and Eve (also known as the Apocalypse of Moses), a Jewish pseudepigraphical text from the first century AD. In this narrative, God commands the angels to bow down to Adam as His image, but Lucifer (Satan) refuses, declaring, “I will not worship an inferior and younger being.” This refusal leads to his fall, underscoring the propriety of venerating God’s image in creation. Remarkably, a parallel account appears in Islamic tradition, as recorded in the Quran (Surah 2:34; 7:11-12; 15:28-33; 17:61; 18:50; 20:116; 38:71-76), where Allah commands the angels to prostrate before Adam, and lblis (Satan) rebels out of pride. These extra-biblical witnesses, while not canonical, affirm an ancient, cross-cultural recognition of Adam’s iconic dignity, aligning with the biblical mandate for angelic homage to God’s image.

Thus, the veneration of icons extends this principle: just as Adam’s image elicits proper honor directed toward God, so do icons of Christ, the Theotokos, and saints reflect divine glory without diverting worship.

2. Divine Command and Approval of Images in Scripture

Scripture explicitly records instances where God commands or approves the creation of images for sacred purposes, debunking the notion that all visual representations are inherently idolatrous. A prime example is the bronze serpent in Numbers 21:8-9, where God instructs Moses: 11 Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.” This image served as a means of healing, prefiguring Christ’s crucifixion (John 3:14-15), and was venerated by the faithful without condemnation-until it was misused as an idol centuries later (2 Kings 18:4).

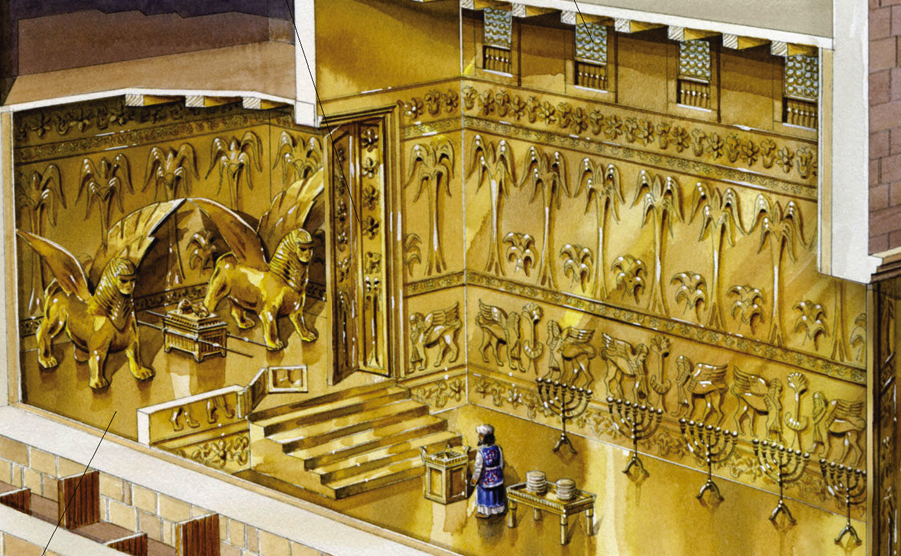

Furthermore, the elaborate artistry in the Tabernacle and Temple demonstrates God’s endorsement of images. In Exodus 25:18-22, God commands the crafting of two golden cherubim (angelic figures) atop the Ark of the Covenant, where He promises to meet with Moses. The Temple, as described in 1 Kings 6:23-35 and 7:25-51, was adorned with carved cherubim, palm trees, open flowers, oxen, and lions-images of heavenly and earthly realities. Ezekiel’s visions (Ezekiel 1:5-28; 10:1-22) similarly depict the divine throne surrounded by living creatures and wheels, inspiring Temple iconography. These elements were not mere decorations but integral to worship, symbolizing the heavenly court and directing the mind toward God. If God Himself ordained such images in His sanctuary, how can the Church’s use of icons be deemed unbiblical?

3. Distinguishing Idolatry from Right Veneration: The Role of Intention

The critical distinction between idolatry and proper veneration lies not in the act itself but in the intention and context, as illustrated by the bronze serpent. Initially a God-ordained image for salvation, it became idolatrous when the people burned incense to it as a deity (2 Kings 18:4), shifting honor from the Creator to the creation. This underscores that veneration (proskuneo) – a Greek term used in Scripture for bowing or homage (the historical English equivalent “worship”) – is permissible toward creatures when it is relative, not absolute.

Proskuneo appears in contexts where it is rightly offered to humans or angels without implying divine worship: for instance, Abraham bows to the Hittites (Genesis 23:7), Joseph receives homage from his brothers (Genesis 37:9-10), and David is venerated by his subjects (1 Chronicles 29:20). Yet it is rejected when it implies idolatry, as when Peter refuses Cornelius’s proskuneo (Acts 10:25-26) or the angel rebukes John (Revelation 19:10; 22:8-9). The intention matters: relative veneration honors God’s image or work in the creature, while absolute worship belongs to God alone (Matthew 4:10). Icons, therefore, receive relative veneration (dulia for saints, hyperdulia for the Theotokos), passing all honor to the prototype-Christ or the saint depicted-ultimately glorifying God.

4. Human Images Post-Resurrection: Access to the Heavenly Realm

In the Old Testament Temple, human figures were notably absent from the iconography, reflecting humanity’s exclusion from the heavenly realm due to sin. The Holy of Holies symbolized God’s unapproachable presence, accessible only to the high priest once a year (Hebrews 9:7). Angels and symbolic creatures adorned the space, but no humans, as mankind had not yet been redeemed and elevated.

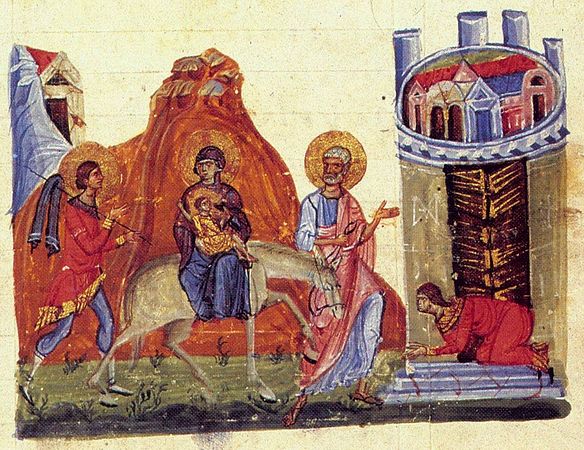

This changes dramatically with Christ’s resurrection and ascension. Hebrews 12:22-24 describes believers approaching “Mount Zion… the heavenly Jerusalem… innumerable angels in festal gathering… the assembly of the firstborn… the spirits of the righteous made perfect.” Through Christ, humans now participate in the angelic realm, seated with Him in heavenly places (Ephesians 2:6). Saints, as deified humans (2 Peter 1:4), join the heavenly liturgy, warranting their depiction in icons. The Incarnation bridges the gap: God becomes visible in human form (John 1:14), allowing human images to represent the sanctified in heaven. Thus, post-resurrection iconography fulfills Old Testament types, portraying the new reality of redeemed humanity in God’s presence.

5. Historical Confirmation in Synagogues and Catacombs

Archaeological evidence from ancient Jewish synagogues and early Christian catacombs affirms the acceptability of artistic representations, countering claims of aniconism in biblical faith. The third-century Dura-Europos synagogue in Syria features vivid frescoes depicting biblical scenes, including Moses, Elijah, and the hand of God-figurative art in a worship space. Similarly, synagogues at Capernaum and Hammath Tiberias show mosaics with zodiac symbols and human figures, indicating that Second Temple Judaism tolerated images when not idolatrous.

Early Christian catacombs in Rome (second to fourth centuries) abound with paintings of Christ as the Good Shepherd, the Virgin Mary, apostles, and martyrs. These were not mere tombs but sites of prayer and veneration, where images facilitated devotion. Such evidence demonstrates continuity from Jewish roots to apostolic Christianity, where art served catechesis and worship without violating the Second Commandment’s prohibition against idols.

6. The Iconic Access to God: From Adam to Christ

Returning to humanity’s iconic nature, Genesis 9:6 (not 6:9, which describes Noah’s righteousness) reaffirms: “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed, for God made man in his own image.” This post-Flood reiteration emphasizes the enduring sanctity of the human image, even after sin.

Theologically, God the Father, being invisible and uncircumscribable, is accessed only through His perfect Icon, Jesus Christ: “He is the image of the invisible God” (Colossians 1:15). Christ declares, “No one comes to the Father except through me… Whoever has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:6-9). Icons of Christ thus make the invisible visible, enabling communion with the divine. This iconic mediation extends to saints, whose images reflect Christ’s light, confirming the biblical principle that all creation images God hierarchically.

7. Veneration of Saints: Relative Honor and the Holy Kiss

Redeemed humans, as saints, merit relative honor (dulia) as participants in divine glory. Scripture enjoins the “holy kiss” as a sign of this: “Greet one another with a holy kiss” (2 Corinthians 13:12; cf. Romans 16:16; 1 Corinthians 16:20; 1 Thessalonians 5:26; 1 Peter 5:14). This gesture symbolizes fraternal veneration, honoring Christ in the believer.

Psalm 2:11-12 further relates kissing to veneration: “Serve the Lord with fear… Kiss the Son, lest he be angry.” In the Septuagint, “kiss” (from ·lj7�l, nashqu) carries connotations of homage or proskune6, urging submission to God’s anointed. Other texts, like 1 Samuel 10:1 (Samuel kisses Saul as king) and 1 Kings 19:18 (faithful who have not “kissed” Baal), distinguish proper from improper veneration. Kissing icons echoes this biblical practice, offering relative honor to saints as “friends of God” (James 2:23), directing all to Christ.

Conclusion

The bishops’ defense of icons, as articulated at the Seventh Ecumenical Council (787 AD), wisely upholds a fundamental biblical theology: the iconic relationship whereby all praise, thanksgiving, and worship return to the Father as the sole origin and cause, through His perfect Icon, Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Spirit {Ephesians 2:18). This aligns with Old Testament teachings on the acceptable use of images, as seen in the Tabernacle, Temple, and bronze serpent. Icons are not innovations but apostolic continuations of Scripture’s iconic worldview, safeguarding against both idolatry and a disembodied spirituality. In venerating icons, the Church proclaims the Incarnation’s triumph, inviting all to behold and honor the divine through the visible.